This version (2018/01/31 13:17) is a draft.

This version (2018/01/31 13:17) is a draft.Approvals: 0/1

This is an old revision of the document!

Linux Primer

- Article written by Balázs Lengyel (VSC Team) <html><br></html>(last update 2017-10-11 by bl).

Note

Please use the Table of Contents or your browsers quick search to find what you’re looking for, as this document is auto-generated from a presentation and context may not always be recognisable without the corresponding talk.

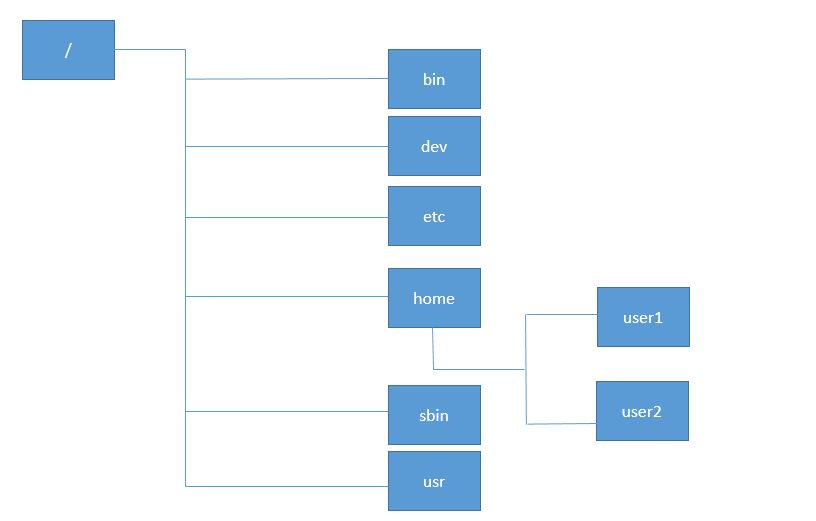

Filesystems

Filesystem 101

The job of filesystems is to keep data in a structured way. Every filesystem has a filesystem root, directories and files. The filesystem root is a special object which acts as an entrypoint for using that filesystem. All other objects (directories and files) are structured below the root.

Two main concepts emerged for using more than one filesystem on a single machine:

<HTML><ol style=“list-style-type: decimal;”></HTML> <HTML><li></HTML><HTML><p></HTML>Special handling (a.k.a Drive letters)<HTML></p></HTML> <HTML><p></HTML>This is how Windows handles filesystems. It explicitly shows which drive you’re working on.<HTML></p></HTML><HTML></li></HTML> <HTML><li></HTML><HTML><p></HTML>Virtual Filesystem<HTML></p></HTML> <HTML><p></HTML>This is a more subtle approach, used by Linux, where you specify in the beginning (booting) which filesystem will be used for which part of the virtual filesystem.<HTML></p></HTML><HTML></li></HTML><HTML></ol></HTML>

Linux’ virtual filesystem tree represents all the files and directories that are reachable from the system. The nice part is that you can work on a Linux machine and not care about whether your file is on the network or on a local filesystem. The main difference for users is the performance delivered by different filesystems.

This is how the (virtual) filesystem looks on Linux:

- Everything starts at the root

- the root is a directory

- “

/” denotes the root directory

- the filesystem has different kinds of objects

- files

- directories

- containers for multiple objects

- links to objects, which either

- add a second name for the same object

- point to a position in the filesystem

- objects can be referenced by their path

- absolute:

/dir1/dir2/object - relative:

dir2/object

- special objects in directories:

.— is a reference to the directory itself..— is a reference to the parent directory

- the system may consist of multiple filesystems

- filesystems may be mounted at any (empty) directory

Further concepts

Next to basic storage and organization of data filesystems have different properties and functionality. Most filesystems provide a way to store and access attributes, different kinds of special files and some filesystems provide various advanced features:

- Attributes

- Ownership

- Access rights

- Filesystem limits

- Size

- Timestamps

- Special files

- device

- fifo pipe

- socket

- Advanced FS features

- data integrity

- device managment

- subvolume support

Filesystem tree

<HTML> <!– ### Mountpoints

Linux presents only one tree for file access - but every filesystems has its own tree!

#### Attaching a filesystem to the current tree: {.incremental}

- takes a filesystem

- `FS` usually a device file or a network address

- takes an empty directory in the current tree

- usually `/mnt/XXX` or `/mnt`

- makes the root of the new filesystem available in place of the empty directory

- `FS` `→ /mnt/`

<div class=incremental>

This process is called mounting.

</div> –> </HTML>

Special filesystems used on VSC

NFS

- old and reliable network filesystem

- much slower than any local filesystem

- simultaneous usage possible

TMPFS

- very fast filesystem

- uses RAM instead of other media

- lost at shutdown

The home directory of the user is located on an NFS filesystem, which ensures that all parts of the cluster have a consistent view of files.

The filesystem behind the $SCRATCH variable is located on a tmpfs filesystem, which is a double-edged sword. On one hand it’s fast, but since it uses RAM as a storage device it does limit the amount of memory available for programs. Also you can only use data stored in a tmpfs only on the host itself.

Shell

Prompt

This is how the prompt looks by default:

[myname@l3_ ~]$

- tells you:

- who you are

- which computer you’re on

- which directory you’re in

- can be configured

- variable

$PS1 - default:

echo $PS1

Ways to get help when you’re stuck:

Most of the time a command doesn’t act as expected, it shows an error message. From this point you have multiple approaches:

- Think about why the program failed - maybe you (un-)intentionally tried to force the program to do something it’s not intended for?

- Just copy that message into your favourite search engine and don’t forget to remove the parts that are specific to your environment (e.g. directory and user names).

- Most programs supports a

-h/--helpflag man <COMMAND>will be available for most programs too, if notman -K <KEYWORD>will search all man-pages that contain the keyword. (FYI: press ‘q’ to quit)- An alternative to

manisinfo <COMMAND>, which is like a browser from the ’80s - Ask colleagues for help

Execution

To execute a program, we call it:

gcc FizzBuzz.c -o FizzBuzz

./FizzBuzz

module load non-existent-module

echo $?

The examples show compiling a program, executing the result, trying to load a module on our cluster and checking if the previous command succeeded.

gccis a program that is in a directory specified by the$PATHvariable and will be found without specifying its exact location../FizzBuzzis a newly compiled executable, which is not found by looking at$PATH, so we explicitly add./, to show that we want to execute it from the current directorymodule load non-existent-modulefails, as the module command can’t findnon-existent-module. Whenever a command fails, itsreturn valueis set to a value other than zero. The manual for some commands has a map from return-value to error-description to aid the user debuging.echo $?is a command that prints the return value of the previous command.

History

Your shell keeps a log of all the commands you executed.

- the

historycommand is used to access this history - for fast reuse of commands try the

<CTRL>-Rkeys or the<Up-Arrow>

Parameters

The default way to apply parameters to a program is to write a space separated list of parameters after the program when calling it.

These parameters are either

- Single-character

- Multi-character

- Strings

where some parameters also take additional arguments.

Combining parameters

For most commands you can combine multiple single-character parameters. This doesn’t change the meaning of the parameters, but is limited to single-character parameters which don’t take extra arguments.

COMMAND -j 2 -a -b -c COMMAND -j 2 -abc

Ordering parameters

One thing to look out for is the order of parameters. Most of the time no specific order is required, but you should look out for things like copying the target over the source file. Also watch out to keep parameters and their arguments together.

COMMAND <SRC> <DEST> # OK COMMAND <DEST> <SRC> # PROBABLY WRONG COMMAND -j 2 --color auto # OK COMMAND -j auto --color 2 # PROBABLY WRONG

Escapes & Quotes

Whenever a parameter has to contain a character that is either unprintable or reserved for the shell, you can use:

- Backslash escape:

- Escapes a character, that would have a special meaning

- Can be used inside of quotes

- Double Quotes:

- Similar to escaping all whitespace characters

- Single Quotes:

- Additionally prevents expansion of variables

COMMAND This\ is\ a\ single\ parameter COMMAND "This is a single parameter" COMMAND 'This is a single parameter'

Aliases

You can define aliases in your shell. These are usually used to shorten names for commands which are used often with a fixed set of parameters or where you have to be careful to get things right. These aliases are accessable as if they were commands.

alias ll='ls -alh' alias rm='rm -i' alias myProject='cd $ProjectDir; testSuite; compile && testSuite; cd -'

After that, you can use the aliases synonymously.

ll # Same as 'ls -alh' rm # Same as 'rm -i' myProject # Same as 'cd $ProjectDir; testSuite; compile && testSuite; cd -'

Patterns

Patterns are an easy way of defining multiple arguments, which are mostly the same. The pattern will match anything in it’s place.

The other concept is a expansion. In this case only defined patterns will be matched.

- the most important patterns are:

- ? — matches one character

- * — matches any character sequence

- the most important expansions are:

- A{1,9}Z — expands to A1Z A9Z

- A{1..9}Z — expands to A1Z A2Z … A9Z

You can try these commands and see what they do. These are all totally safe, even if you modify the arguments.

ls file.??? ls *.*

echo {{A..Z},{a..z}} echo {{A,B},{X,Y}}

echo {A..Z},{a..z} echo {A,B}{X,Y}

Regular Expressions

Often you need to specify some string, but patterns and expansions aren’t enough, to cover all possibilities. In these cases you can use a regular expression also known as regex. These regexes are used by editors for search and replace, the egrep command for filtering through files and inside many scripts to validate parameters.

.+ # Match any character, once or more \. # match a dot (A|a)p{2}le # apple, Apple ^[^aeiouAEIOU]+$ # any line of only non-vowels

For a detailed explanation see Wikipedia, Regular-expressions.info or try regex101.

If you want to challenge yourself, try Regex Crossword!

Control Flow

In the shell language there are a few ways to organize the execution path. The most important ones are:

- chaining of commands

- looping constructs

- conditionals (if/case)

Chaining Commands

The simplest mechanism for control flow is to chain commands together in a simple if COMMAND then NEXTCOMMAND else ERRORCOMMAND. Since this would be cumbersome to write, most shells provide simple syntax for this: COMMAND && NEXTCOMMAND || ERRORCOMMAND and if a command should be run without relying on the return velue of its predecessor it’s written: COMMAND; NEXTCOMMAND. And if you only want to execute further commands in one case (but not the other), you don’t even have to specify both branches.

false ; echo "Should I be Printed?" false && echo "Should I be Printed?" false || echo "Should I be Printed?"

Should I be Printed? Should I be Printed?

Loops

The other way to execute commands conditionally are loops. You can loop over files, numeric arguments, until a either the loop condition is false or a break is encountered.

for i in * do mv $i{,.bak} done

while true do echo "Annoying Hello World" sleep 3 done

for i in *; do mv $i{,.bak}; done while true; do echo "Annoying Hello World"; sleep 3; done

Conditionals

If is similar to the previous chaining of commands, except that it is more verbose and nicer to read if you have many commands to execute one branch of the decision. For more conditions the elif (else if) statement can be used. If you use a lot of elifs and you only check one variable with them, you should consider using a case statement.

if [ $VARIABLE1 ] then COMMAND1 elif [ $VARIABLE2 ] COMMAND2 else COMMAND3 fi

Case statements are for querying all states of a single variable and making a decision based on that. It can match some simple expansions, which do NOT follow the general syntax of bash expansions. Also it processes alternative matches when seperated with | (pipe character).

case $VARIABLE in [0-9] | [1-2][0-9]) COMMAND1 ;; *) COMMAND2 ;; esac

Streams

Redirects

Write output to a file or file-descriptor

| Command | Redirect | Append | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| program | > std.log | >> std.log | redirect stdout to a file |

| program | 2> err.log | 2>> err.log | redirect stderr to a file |

| program | 2>&1 | redirect stderr to stdout |

Pipes

Write output into the input-stream of another process

| Command | Pipe | Description |

|---|---|---|

| program | | grep -i foo | pipe stdout into grep |

| program | | tee file1 file2 | overwrite files and stdout |

| program | | tee -a file | append to files and stdout |

Environment Variables

Setting, getting and unsetting

Set

LANG=en_US.UTF-8 bash export LANG=en_US.UTF-8

Get

env echo ${LANG} echo $PWD

Unset

unset LANG env -u LANG

Use cases

Some variables that could affect you are:

$EDITOR # the default editor for the CLI $PAGER # utility to read long streams $PATH # program paths, in priority order

if you’re aiming for programming, these could be more interesting:

$LIBRARY_PATH # libraries to link by the compiler $LD_LIBRARY_PATH # libraries to link at runtime $CC # sometimes used to set default C compiler $CFLAGS # default flags for compiling C

<HTML> <div class=“incremental”> <div> <hr color=“lightgrey” class=“slidy” /> </HTML>

if you have a lot of self-compiled binaries:

export PATH="./:$HOME/bin/:$PATH"

<HTML> </div> </div> </HTML>

Basic command line programs

Looking around

Looking through files is done with thelscommand under Linux, which is an abreviation forlist.

By default (meaning without parameters) the ls command shows the content in the current directory. It does hide elements starting with a dot though. These hidden elements can be shown by adding the -a parameter, which stands for all. If you want detailed information about the elements, add the -l parameter for long listing. You can also specify a file/directory which you want to examine, by just appending the path to the command.

$ ls # shows files and directories testdir test $ ls -a # includes hidden ones . .. testdir test $ ls -l # detailed view drwxr-xr-x 1 myuser p12345 0 Apr 13 2017 testdir -rw-r--r-- 1 myuser p12345 4 Apr 13 11:55 test $ ls /tmp/ allinea-USERNAME ssh-6E553lWZCM ssh-C6a754pJ1d systemd-private-a4214393983d448fbdc689791806519c-ntpd.service-LrAgBP tmp7CJZRA yum_save_tx.2017-04-03.12-07.VCUowf.yumtx $ ls -alh ~ drwxr-xr-x 5 myuser mygroup 45 Jan 30 2017 .allinea -rw------- 1 myuser mygroup 21K May 3 17:14 .bash_history -rw-r----- 1 myuser mygroup 231 Dec 2 2016 .bashrc drwx------ 1 myuser mygroup 76 Aug 22 2017 Simulation drwx------ 2 myuser mygroup 76 Dec 12 2016 .ssh

Moving around

Moving through directories is done with thecdcommand, which stands forchange directory.

The cd command can be called without any arguments, in which case it just switches to the home directory. Otherwise it takes a absolute (starting with a dash) or relative path as an argument and switches to that directory. The argument - (just a single dash) will cause cd to switch to the previous directory. This can be used to alternate between two directories without typing their path’s every time.

$ cd /bin # go to an absolute directory $ cd [~] # go home $ cd - # go to previous directory

Copying & moving files around

Copying and moving files and directories is done with thecpandmvcommands, which stand forcopyandmoverespectively.

Both commands take at least two parameters, which correspond to the <SOURCE> and <DESTINATION> files or directories. For cp to work with directories as a source, it needs the -r (recursive) or -a (archive) flag.

Beware of the pitfalls! you can overwrite data and therefor lose it, without getting any confirmation prompt! If in doubt use-i(interactive) flag.

$ mv old new # rename old to new

$ mv old dir/ # move old into dir

$ mv file1 file2 # overwrite file2 with file1

# (BEWARE)

$ cp -i input input.bak # input to input.bak $ cp -i input backup/ # input into backup $ cp -a dir1/ dir2 # exact copy of dir1

Creating and deleting

directories

creating directories is done with themkdircommand, which stands formake directory.

The mkdir command takes an optional -p (parents) parameter and a path. When optional parameter is given, it will create all the ancestors of the specified directory aswell. Otherwise the command fails if the directory either exists already or its parent doesn’t exist either.

deleting directories is done with thermdircommand, which stands forremove directory.

This command removes the specified directory, but only if it’s already empty. it can also take an optional -p parameter, in which case it removes the specified directory and all the ancestors you included.

Finding stuff

To look at everything

- in your home directory

- and nested up to three levels deep inside it

- that ends in

.txt - or starts with

log_ - and is an ordinary file

- concatenated as one stream:

find \ ~ \ -maxdepth 3 \ -iname "*.txt" \ -or -iname "log_*" \ -type f \ -exec cat '{}' \; | less

find \ ~ \ -maxdepth 3 \ -iname "*.txt" \ -or -iname "log_*" \ -type f \ -exec cat '{}' + | less

Contents of files

viewing is done by thelesscommand:

concatenating is done by thecatcommand:

$ less file.txt # exit with 'q' $ less -R file.txt # keep colors $ cat file1 file2 | less

$ cat file $ cat -A printable $ cat -n numbered

$ echo "VSC is great" > file $ cat file VSC is great

$ echo "VSC is awesome" >> file $ cat file VSC is great VSC is awesome

$ cat file | grep awesome VSC is awesome

$ grep awesome file VSC is awesome

Space accounting

viewing used space is done by thedu(disk usage) command:

viewing free space is done by thedf(disk free) command:

$ du -h file1 file2 # human readable output $ du -s dir # summarize

$ df -h # human readable output $ df -t nfs # only list filesystems of a type

Recap

$ mv space.log space.log.bak

$ df -h | grep "lv12345\|lv54321" > space.log

$ cat space.log

nfs05.ib.cluster:/e/lv12345 200G 185G 16G 93% /home/lv12345 nfs04.ib.cluster:/e/lv54321 1000G 979G 22G 98% /home/lv54321

we do this often, let’s wrap it up!

Recap++

$ mv space.log space.log.bak

$ df -h | grep "lv12345\|lv54321" > space.log

$ cat space.log

nfs05.ib.cluster:/e/lv12345 200G 185G 16G 93% /home/lv12345 nfs04.ib.cluster:/e/lv54321 1000G 979G 22G 98% /home/lv54321

we do this often, let’s wrap it up!

$ echo '#!/bin/bash' > spacelog.sh $ echo 'mv space.log space.log.bak' >> spacelog.sh $ echo 'df -h | grep "lv12345\|lv54321" > space.log' >> spacelog.sh $ echo 'cat space.log' >> spacelog.sh

$ chmod +x spacelog.sh

$ ./spacelog.sh

Sed and awk

sed (stream editor) and awk are powerful tools when working with the command line

$ mycommand | sed "..."

$ mycommand | awk '{...}'

Using sed and awk in action

| program | command | description |

|---|---|---|

| sed | s/old/new/ | replace old with new |

| sed | /from/,/to/ s/old/new/ | replace old with new, between from and to |

| awk | 'print $5 $3' | print columns 5 and 3 of every line |

Example script:

#!/bin/bash mv space.log space.log.bak df -h | grep "lv12345\|lv54321" > space.log cat space.log

#!/bin/bash mv space.log space.log.bak df -h | grep "lv12345\|lv54321" > space.log cat space.log | sed "s|/home/lv12345|ProjectA|" \ | awk '{print $6, "free:", $4}' \ | column -t

<HTML> <!– ### Sort and uniq

sort and uniq (unique) are used to sort and uniquify adjacent lines

–> </HTML>

Scripting

Ownership and Permissions

Just to ensure that you are able to run your scripts

chown

Change the owner of files and directories by:

chown -R user:group dirs files # only works with root privilages

chmod

Change the mode of files and directories by:

chmod -R u=rwx,g+w,o-rwx dirs files chmod 640 files chmod 750 dirs chmod 750 executables

Shebang

A little test program, which we mark as executable and hand it over to the corresponding interpreter:

cat << EOF > test.sh echo "${LANG}" echo "${PATH}" EOF

chmod +x test.sh

bash test.sh

Don’t we have an OS, capable of executing everything it recognises as an executable?

Yes, we do!

cat << EOF > test.sh #!/bin/bash echo "${LANG}" echo "${PATH}" EOF

chmod +x test.sh

./test.sh

Functions (more like procedures)

Programming in bash would be cumbersome without functions, so here we go:

allNumbersFromTo () { echo "1 2 3" }

This isn’t good, as were only getting a fixed amount of numbers. Let’s try a recursive approach:

allNumbersFromTo () { num=$1 max=$2 echo "${num}" if [ $num -lt $max ]; then allNumbersFromTo "$(($num + 1))" $max fi }

allNumbersFromTo () { min=$1 max=$2 for num in $(seq $min $max) do echo "${num}" done }

allNumbersFromTo 1 10

Editors

General

- Many different editors

- Unique (dis-)advantages

- Different look and feel

- Editors should provide us with

- Simple text editing

- Copy and paste

- Search and replace

- Saving changes

- Wide availability

Two editors that satisfy our needs:

- nano

- vim

Common starting point

nano filename

vim filename

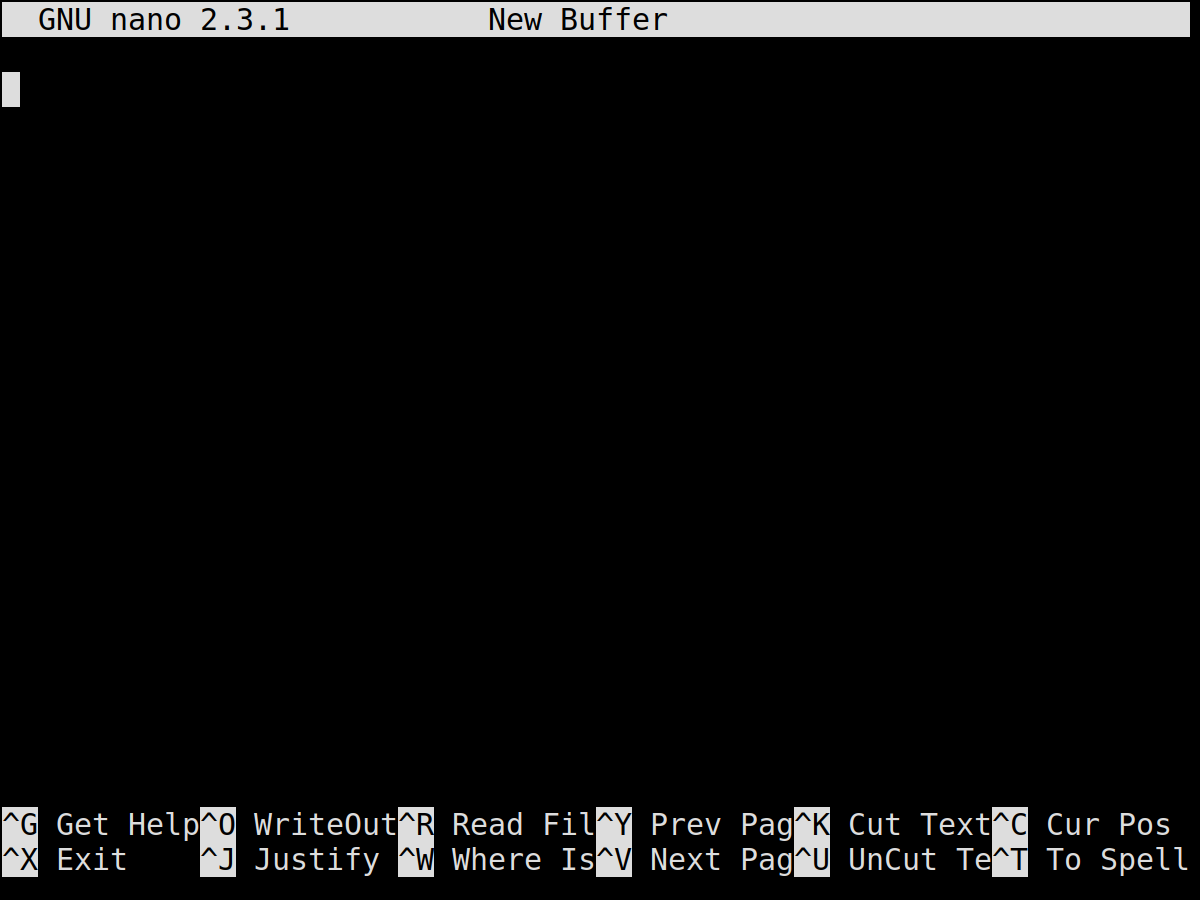

Nano

Nano explained

This editor is focused on being easy to use, but still providing every feature a user might need.

Interface

The interface consists of four parts, namely from top to bottom:

- Title bar

- Text area

- Command line

- Key bindings

Usage

Nothing special, key-bindings visible while editing

| Feature | Usage |

|---|---|

| Navigation | Arrow keys |

| Actual editing | Typing text, as usual |

| Cut/Paste line | <CTRL>+k / <CTRL>+u |

| … | explained in key bindings field |

Short

Use this editor if you are new to the command line.

It is straight forward, but can be extended on the way.

- Auto-indentation

- Syntax highlighting

- Multi-buffer

Vi(m)

Vi(m) explained

This editor is focused on productivity and efficiency, providing everything a user might need.

Interface

The simple interface consists of two parts:

- Text area

- Command line

Since this editor is very easy to extend, after setting up a few plugins, it will probably look quite different!

Usage

This is a multimode editor, you’ll have to switch modes whenever you change what you want to do.

| Feature | Usage |

|---|---|

| Navigation | Arrow keys |

| Writing | change to input mode, then write as usual |

| Commands | exit current mode, press : |

| … | explained on next slide |

Short

Use this editor if you like a challenge.

It is fast and very nice — but you’ll sometimes get hurt on the way.

- Auto-indentation, Syntax highlighting, Multi-buffer – just like nano

- File/Project Management

- Use a plugin manager

Vi(m) modes and keys

- any mode:

- back to the default mode:

<ESC>

- command mode (followed by

<RETURN>):- save current file:

w [filename] - quit the editor

- after saving:

q - without confirmation:

q!

- help:

h [topic], e.g.h tutorial - search and replace:

%s/old/new/gc

- default mode:

- enter input mode:

i - enter command mode:

:(colon) - mark

- character-wise:

v - line-wise:

<SHIFT>-v

- delete

- character-wise:

x - line-wise:

dd - marked content:

d

- search:

/abc

.bashrc

.bashrc

# .bashrc # Source global definitions if [ -f /etc/bashrc ]; then . /etc/bashrc fi # User specific aliases and functions alias sq='squeue -u $USER' alias rm='rm -i' export PATH="./:$HOME/bin:$PATH"

<HTML> <!– ## Legal {.slidy}

### Copyleft & Copyright {.slidy}

<div class=slidy> - wikipedia — “Sadegh 1990 hosseini”: - [CC-Attribution-ShareAlike (CC-BY-SA)](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) - [Directory Tree](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Linux_directories.jpg) - VSC — Lengyel Balazs: - No explicit license - Screenshots </div> –> </HTML>